Maintaining good health—including good oral health—as long as possible is a critical component of aging in place.

“The teeth are made from stern stuff. They can withstand floods, fires, even centuries in the grave. But the teeth are no match for the slow-motion catastrophe that is a life of poverty: its burdens, distractions, diseases, privations, low expectations, transience, the addictive antidotes that offer temporary relief at usurious rates.” – Mary Otto in Teeth: The Story of Beauty, Inequality, and the Struggle for Oral Health in America.

Fall is apple season. As the weather turns cooler, Americans look forward to picking them, eating them, and “putting them up,” as my grandmother would say, for the winter months. Sinking your teeth into a crisp, juicy apple is one of life’s simple pleasures.

Can you imagine never being able to do that again?

Not long ago, Denise LeClair of Chesterfield, Virginia, was resigned to never eating her favorite fruits and vegetables. The 77-year-old retiree had last seen a dentist 18 years ago, during a brief period when she had dental insurance through an employer. But in the years since, she’s been unable to afford even a routine cleaning without dental coverage and her teeth began to decline. A few of her teeth began to loosen, and she feared the gradual loss of what she considers some of her most important assets.

“Some of my front teeth were kind of a mess,” LeClair said. At one point, she consulted a dentist. “They told me it would take about $20,000 to fix everything,” she said. With no savings and on a fixed income, this was out of the question. So she resorted to eating mostly soft, processed foods.

In addition to her physical discomfort, LeClair became self-conscious of her appearance, and began to withdraw socially. As anyone who works with older adults can tell you, lack of good nutrition and social isolation are two preventable factors that, over time, can contribute to a decline in overall physical and mental health among seniors. Left unaddressed, the decline escalates in most cases, and can lead to institutionalization or premature death.

Unfortunately, LeClair’s story is not unique. Similar stories play out across the country every year among millions of Americans age 65 and older, according to the 2018 Oral Health America report, A State of Decay: Are Older Americans Coming of Age Without Oral Healthcare? The report assesses the oral health status of older adults in each state by household income levels, highlights the barriers to good oral health, and ultimately serves to illustrate the need for a comprehensive dental insurance benefit for seniors at the state and national levels.

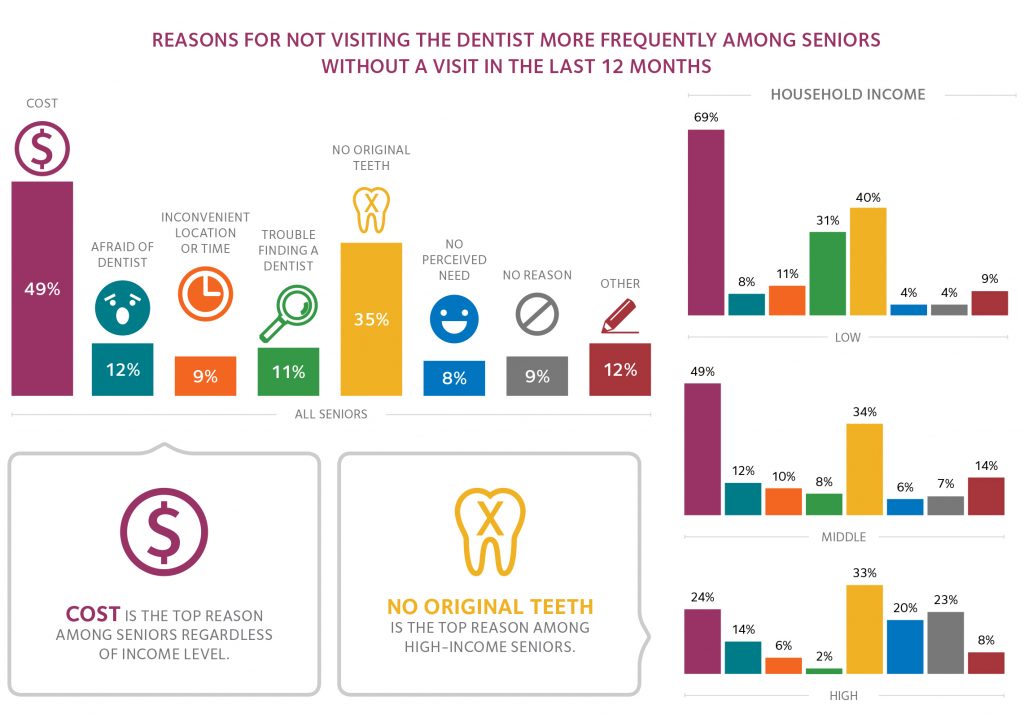

Those having dental insurance may take for granted a twice-yearly preventive-care visit to the dentist. But for many seniors on a fixed income—and even more so for seniors on the lower end of the economic spectrum—a routine cleaning is a luxury. Forty-nine percent of seniors 65 and older who have not seen a dentist in a 12-month period cite cost as the No. 1 reason for not visiting the dentist more frequently. That number skyrockets to 69 percent of low-income seniors, according to the American Dental Association’s Health Policy Institute.

Numerous studies show an inextricable link between oral health and overall health and well-being. A recent report by Tooth Wisdom, a project of Oral Health America, shows a direct correlation between gum disease and other chronic, life-shortening health conditions such as diabetes, heart disease and stroke, and stomach ulcers. Poor tooth quality can be painful and make speaking, chewing, and swallowing difficult. It can also lead to the downward spiral of tooth loss, poor nutrition and digestion, and low self-esteem. According to A State of Decay, a shocking 33 percent of older adults in America have lost six or more teeth.

In a 2016 study by the Pew Research Center, 61 percent of Americans 65 and older said that they want to “age in place,” or stay in their own homes as long as possible. Maintaining good health—including good oral health—as long as possible, then, is a critical component of aging in place.

Plus, as with primary health care, covering preventive oral health services makes sound economic sense. The costs of more frequent visits to the dentist for preventive care would be significantly less than more expensive and invasive treatments required due to neglect of oral health. Covering these services would lead to fewer visits to hospital emergency rooms as well. It would seem that establishing a comprehensive dental benefit for older Americans would be a no-brainer.

How Did the Oral Health Problem Become so Acute?

In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Social Security Act Amendments into law. By so doing, the administration established Medicare, a health insurance program for the elderly; and Medicaid, a health insurance program for the poor. Paid for through taxes, these programs have brought financial relief and peace of mind to millions of older and low-income Americans seeking medical care.

Even so, neither is a panacea. There are major gaps in coverage, and dental care is a big one. While Medicare is administered at the federal level, each state has the latitude to determine what benefits they will pay for under their individual Medicaid programs. Funding for both programs falls under frequent scrutiny whenever state and federal budget allocations are negotiated, and is often politicized to the detriment of those who need them most.

Medicare generally only covers emergency dental services, which amounts to paying primarily for tooth extractions for most older Americans. This is the case even when dental procedures have been prescribed as a requirement before undergoing a surgery that Medicare will pay for, according to the health policy advocacy group Families USA.

While Medicaid has made great strides in covering typical dental services for children of low-income families, less than half of all states currently provide comprehensive dental care for low-income adults. In the suburbs of Richmond, Virginia, where Denise LeClair lives, Medicaid covers only emergency dental services, like tooth extractions, for adults.

Families USA reports that one out of every five American seniors has untreated tooth decay; and two out of five low-income seniors have complete tooth loss. With the costs of typical dental procedures running from around $150 for a cleaning and fluoride application, $200 for a filling, and upwards of $5,000 for a tooth replacement, older adults—especially those on the lower end of the economic spectrum—have tough decisions to make when juggling the prospect of hefty dental bills alongside monthly rent, utilities, and groceries. As a result, most simply put off seeing a dentist, or opt for tooth extraction.

When tooth pain becomes unbearable, many underinsured older adults seek care in the hospital emergency room. Besides being costly, the ER provides no permanent solutions—and may unintentionally create new problems. As most ERs lack dental equipment, the primary treatment for those presenting with tooth pain is a prescription for painkillers. These drugs only mask the problem for a short time, and could contribute new victims to the national opioid epidemic if the cycle isn’t broken.

What Role Can Community Development Organizations Play?

Community development organizations (CDOs) can, and often do, concern themselves with improving the health and well-being of the residents they serve. In a recent survey, NeighborWorks—a membership and support network for more than 245 nonprofit CDOs nationwide—found that, while its members’ primary line of business is affordable housing, 89 percent offered some sort of health and wellness program to residents of their rental communities. These services are typically provided through a combination of direct service and partnerships with health providers in the community.

LeClair is lucky to have found one such rental community. For the past six years, she has rented an apartment in one of the Better Housing Coalition’s (BHC) senior rental communities. Headquartered in Richmond, BHC owns and manages 16 affordable rental communities, eight of which are for lower-income seniors. In addition to housing, residents of BHC rental communities are offered a variety of resident support services to assist them in achieving their educational, economic, and health goals. In the case of its senior residents, BHC coordinates the delivery of health and wellness programs with a number of service providers in the local community.

With average annual incomes of only $14,000, most of BHC’s senior residents can’t afford dental insurance. Observing a growing unmet need for oral health care services among its senior residents, BHC forged a partnership a few years ago with the Lucy Corr Dental

“Most of our patients received good dental care earlier in their lives, but largely due to costs and the lack of dental insurance, we typically find there has been a lapse of between two to five years since a new patient was last seen by a dentist,” said Dr. Patricia Bonwell, a registered dental hygienist and gerontologist, and the clinic’s coordinator.

The clinic serves an average of 412 active patients annually, taking appointments a few days a week. In addition to the clinic’s six part-time staff members, the clinic is an instructional site for the rotation of Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) School of Dentistry’s dental and dental hygiene students. It provides preventive services such as screenings, X-rays, cleanings, and fluoridation along with restorations (fillings) and dentures.

“Our biggest concern with older patients is their ability to get proper nutrition,” said Bonwell. “Helping them retain as many of their natural teeth as possible, while remaining infection free and functional is an important step in making that happen.” Since 2011, the Lucy Corr Dental Clinic has provided an estimated $1 million in free dental services to its patients and has established over 25 partnerships with area geriatric programs and older adult housing sites, says Bonwell.

The icing on the cake for the patients is that “without fail, all of our residents have returned from their visits to Lucy Corr overjoyed about their experience there,” says Joyce Jackson, vice president of community social work at BHC. Jackson believes that their delight can be attributed to the clinic’s practitioners’ ability to “take a respectful and gentle approach to the senior patients, which reduces their anxiety levels, and greatly exceeds expectations.”

LeClair agrees. Lucy Corr “was a godsend,” she says. Though some of her teeth had deteriorated beyond repair, she is now taking good care of her remaining teeth through preventive visits every six months. “I’m a happy camper,” she says. Her diet has improved, too.

Oral Health Care: Barriers to Access

The outcome for too many older adults with poor oral health is not positive, however. Because many dentists are reluctant to take on patients who are unable to pay, low-income residents must rely on their community’s dental “safety net,” as free clinics and community health centers are called. According to the nonprofit Virginia Health Care Foundation(VHCF), 66 Virginia localities currently have no dental safety net for residents; and, while 67 localities have a community dental provider, in many cases services are offered only on a part-time basis. That makes for months-long wait lists for an appointment, which can seem like an eternity to someone in pain.

With so much demand and so little supply, CDOs can be stymied, despite their best efforts, to help residents get access to dental services in their communities. One example is Community Housing Partners (CHP), a nonprofit affordable housing developer in Southwestern Virginia.

CHP is headquartered in Christiansburg, Virginia, the county seat of Montgomery County. The county’s population is 97,653 (as of the 2015 census), 24 percent of whom live below the poverty line. VHCF shows only one dental safety net clinic serving the entire county. To put this into further perspective, the 2018 County Health Rankings and Roadmaps Program(a collaboration between the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute) shows a population-to-dentist ratio of 2,290:1 in Montgomery County. A ratio this high poses a serious access problem, even for those with insurance.

CHP no longer includes direct access to oral health care for seniors in its programming, but at one time it did, according to Tiffany Slusher, CHP’s director of programs. In the past, CHP secured funds to form a pool of donations that senior residents could access to pay for dental services, and they negotiated reduced rates with local oral health providers who agreed to see their residents. Even so, “the need was so great that the funds were quickly exhausted,” Slusher said. Then, too, they found that the fixed sums awarded to eligible residents did not always contribute toward CHP’s intended outcome of achieving better oral health for its seniors. “Despite the reduced service rates, the costs far outweighed the patient subsidies in many cases, and the patients often defaulted to tooth extraction.”

Needed: A Permanent Solution

A more sustainable solution for lower-income adults aged 65 and older would be for Medicare and Medicaid to include a comprehensive adult oral health benefit for program enrollees. The Virginia Oral Health Coalition is leading such a push in Virginia, which recently voted to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. To date, 78 public, private, and nonprofit health organizations have signed on to a support letter drafted by the coalition, addressed to Gov. Ralph Northam.

Likewise, advocacy groups are lobbying the federal government to expand Medicare to include oral health coverage as well. One of these is the DentaQuest Foundation, which launched a strategic initiative called Oral Health 2020. Among the initiative’s goals are for Medicare to include an extensive dental benefit for enrollees by the year 2020, and for at least 30 states to have implemented an extensive Medicaid adult dental benefit by that time.

If we believe that housing and health are inextricably linked, that oral health and overall health are tied to each other, and that senior residents of our communities should be able to age in place to the best of their abilities as long as possible, it follows that advocating for better oral health care for older Americans is a responsible, humane and sensible thing to do.